Studies

My current research includes three practice-based projects, each one centering on an alternative reading of a key work by a particular experimental artist or scientist. These works are Henry S. Fitch’s Autecology of the Copperhead (1960), Lee Lozano’s daily notebooks from the late 1960s, and J.H. van’t Hoff’s theory of the tetrahedral carbon and his related lecture Imagination in Science (1878). In the descriptions that follow, I contextualize these projects and address some of the ways I understand them to relate to each other.

Another Autecology of the Copperhead

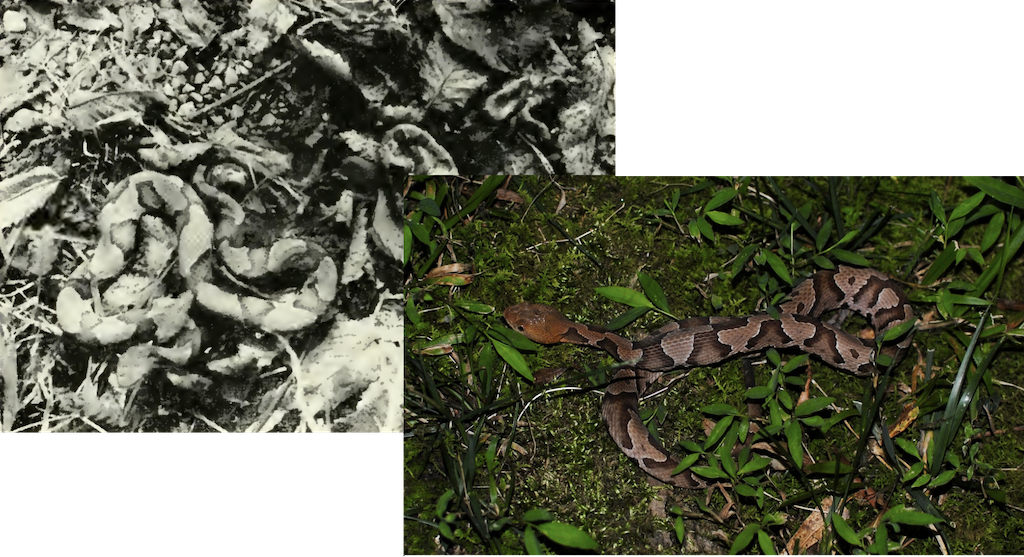

Despite persistent effort to study the copperhead, progress was slow, especially in the early stages of the investigation. Copperheads were rarely seen engaged in their normal activities, and even when such individuals were found, observing them proved remarkably unrewarding. A copperhead found by chance usually lay motionless for long periods either having “frozen” in the usual reaction to any alarm, or merely resting—the sluggish behavior that is characteristic of the species. Attempting to observe such a snake severely tried the patience of the investigator. When the snake finally began to move, it might soon be irretrievably lost because of the perfection with which it blended with its background, and the dense concealing vegetation and other cover in the situations frequented.

— Henry S. Fitch, Autecology of the Copperhead

I have always loved reptiles, and I am especially fond of snakes. I once thought I might be a biologist. Growing up in North Carolina, I encountered snakes often. Rarely, though, do I ever remember seeing a copperhead. I first encountered Fitch’s Autecology of the Copperhead in the summer of 2020, and upon reading it, I instantly sensed a kindred spirit. Despite my enthusiasm for snakes, though, I didn’t seek out the book for pleasure or entertainment. I was dealing with a problem, and I needed trusted advice.

Fitch is indeed regarded as a trusted figure in the community of scientists and naturalists with whom he interacted across his career. Autecology of the Copperhead is a long-term ecological study of a particular population of copperheads on the University of Kansas Natural History Reservation. While many of Fitch’s insights about the species may seem intuitive now, it was precisely his dedication to long-term study that influenced public perception of snakes, their role in scientific research, and conservation efforts that advocate for their value. Autecology includes detailed discussion of copperhead habitat, behavior, anatomy, public perception, growth, and perceived dangerousness. In other words, Fitch embarks upon a major ecological study of a controversial organism, ultimately dedicating a significant amount of his career to this creature.

In July of 2020, at dusk, I was sitting outside with my children in our backyard. My daughters, 4 and 7 years old at the time, were playing in the sandbox. My son, then 9, was running around the yard. I think he was chasing fireflies. I remember I was wearing socks but no shoes. Then, one of my daughters saw a copperhead near the sandbox. I froze, and the kids panicked. I asked everyone to stay still while I went over and picked up my youngest daughter. As I started to carry her toward the house, though, another copperhead appeared in my way. I got my daughter to safety on the deck, then I went back for my other daughter. We had spotted at least four copperheads by the time I got everyone back to the house. It would have been funny if it hadn’t been so upsetting. From the safety of an elevated deck, we spent the next hour watching the snakes. Over the next few days, we observed their emergence at this specific time. We noticed that the snakes seemed to come out at the same time every night and then disappear just as quickly as they appeared. There was no danger during the day. My older daughter started to document when and where we saw snakes. Unfortunately, they seemed to congregate around the sandbox. I didn’t set out to turn this situation into a major project, but it began to evolve in that direction.

Like many people, I spent more time at home during the pandemic. As someone who cherishes mundane aspects of everyday life, I found new details to notice. But, for the first time in my life, I also felt I was beginning to exhaust the possibility of finding new details or new perspectives. I was certainly fortunate to be able to take the time to attend so closely to something as oddly specific as snake routines, but—at first—I have to admit that I felt very unlucky about the project that seemed to be nominating itself to me. The pandemic would end up inspiring a variety of forms of isolation writing while I was just dealing with what seemed like an incomprehensible number of snakes. Yet, as the project became something, I was also iteratively reminded of my complex relationship to the land I call my home.

There is a forested area just beyond our yard, and beyond that is a busy road. So the snakes had places to den during the daytime. I would watch them make their way from the back fence to the sandbox at dusk. I bought a snake grabber, buckets, and a new flashlight. In the summer of 2020, I relocated 20 copperheads to a local nature preserve. (Before doing this, I had to research how many venomous snakes I could transport at a given time without a license).

In 2021, I relocated 15 more snakes. I only moved snakes that spent significant time near the house. That summer, I started walking through the yard with a flashlight and a camera to more closely observe snake behavior. Throughout the process, I wrote in composition books left over from my kids’ school supplies. I didn’t understand this writing to have much significance at the time, and I took notes in books that I later lost. I sought advice locally and read and reread Autecology, which I liked because of the way it presented detailed scientific research while also seeming like a strange endurance art project. Later, I would be strongly influenced by Vinciane Despret’s writing after a friend recommended it to me.

Like many scientists, Fitch clearly cares for the creatures he studies, and while he talks of exerting control efforts when absolutely necessary, he unsubtly advocates for coexisting with the copperhead throughout the book. He makes arguments by placing anecdotal evidence alongside more standard scientific evidence and his own experience:

In localities where copperheads are scarce they are more feared. Persons in suburban communities, who lack first-hand familiarity with snakes, and know the copperhead only by its fearsome reputation, are those most affected. Oliver (1958:46) stated: “It is no exaggeration to say that there are thousands of people around the New York area alone who are terrified by the possibility of an encounter with a Copperhead. Last year I was consulted by two different persons who were considering selling their homes because of reports of Copperheads on their property. One lived in a section where no Copperheads had been found in twenty years, but a large milk snake was killed in her yard by a policeman who said it was Copperhead. (247)

As I began to feel more in control of the snake problem, I started to notice details about Fitch’s snake writing that I really liked, and I felt authorized to imitate and experiment with the ways he documented snake activity as a scientist. Several features of his project appealed to me as a model: it isn’t flashy, it requires long-term investment, it highlights unusual or unexpected care practices, and it involves real experiments but is still organized by practices drawn from natural history. I also began to feel authorized to imagine my own response to the situation unfolding in my yard even as it defamiliarized my assumed place in a highly specific ecosystem:

To my knowledge the copperhead has never been subjected to systematic control operations, but in the course of my field work I received several inquiries as to how such control operations should be carried out. Details of the copperhead’s natural history and ecology such as those set forth in this report provide a background essential in the planning of any control. (251)

In other words, I started to get beyond a strict reading of Fitch’s work and its historical context and really did allow myself to reimagine it as an endurance art project. This reimagining helped me to describe what I was doing, as I could hardly articulate what I was trying to accomplish with my “July project” other than observe snakes and decide which ones to relocate. The practical details kept obscuring my ability to explain my goals or to do more than simply record my actions. When walking in the yard, for example, I tried to have a gentle presence and step softly, yet I was always carrying quite a lot of clunky stuff. I couldn’t write in the dark while also walking carefully and holding a snake grabber, a bucket, and a flashlight. Surmounting highly specific practical issues became the project, and at that point Fitch’s story couldn’t really give me any more useful information. To my knowledge, he didn’t do a long-term study of the nocturnal routines of copperheads, and a large gap in time separated our studies anyway.

For all of the ominousness that might be implied by saying that I observe the nocturnal routines of snakes, my nighttime walks actually reveal snakes engaged in behavior that seems both natural and exuberant. It conflicts with the general description of copperhead behavior that Fitch emphasizes. They move quickly. They hardly seem to notice me even when I get close. They are so focused on other things that they would probably crawl right over my foot if I were in their way. This behavior is well known, but actually witnessing this behavior time and time again, has a significant effect. I became somewhat captivated by the pit viper sensorium.

In Spring 2022, mole hills exploded throughout the yard. I had probably removed too many snakes. For the first time, I started to worry that no snakes would return in the summer. I didn’t relocate any snakes in 2022, and I only observed 3 different copperheads in July. Thus, I observed them each more carefully than in previous years, noting subtle differences in their markings and patterns of movement. I was on crutches at the time, though, so, again, the strategies I had developed for observation had to be reworked. If I wanted to observe the snakes closely, then I would have to deal with being more of a disturbance to them and slower than usual. Nonetheless, I recorded voice notes of my observations and the conditions that made observation difficult, and I shared them with friends. I listened closely to the sound of the cicadas in the background. I became confident about when I could count on seeing snakes in the yard and when it would be safe to walk around uncarefully.

Hopefully capturing some of the absurdity of the situation, I made some collages to illustrate the ways in which I understood myself to be reinterpreting the fundamentals of Fitch’s approach to studying snake ecology. Yet, it is probably worth stating outright that I wonder how he might have interpreted my project. If I were to receive a bite while relocating a snake, it might garner some sympathy. If I were to receive a bite while doing my nightly walk through the yard with my flashlight, I suspect I would receive less sympathy. Why engage in a “scientific” project like this if it isn’t producing any new knowledge about nocturnal snake behavior? (asks the scientist) Is this all just an elaborate and warped recreation of Vito Acconci’s Following Piece? (asks the artist) When does it all go too far? Or, in other words, do we have a reading frame to make its significance legible? How do strange daily practices become naturalized, and what are the conditions that might lead those practices to be finally exhausted, questioned, or replaced?

Snakes are certainly associated with an abundance of symbolic meanings. The meanings they invoke across cultures are definitely important to my writing. But, in my view, only from a cold distance would, say, a Freudian reading of my project be interesting or amusing. From the paradoxically warm proximity of the scientific gaze that is always emerging in Autecology, copperheads can be conceptualized in an appealing, and more dimensional, framework.

My sense of experiment is heavily inflected by twentieth-century French philosophy of science (particularly the work of Jean Cavaillès and Raymond Ruyer), my work in the Speculative Sensation lab at Duke, and my long-term study of Clark Coolidge and Bernadette Mayer’s poetry. As a result, I am driven by a desire to develop processes by which one can make nonintuitive information legible. The snake project has certainly changed the way I relate to my sense of home as well as my sense of what “autecology” can be as a mode of experimental ecopoetics. But at the level of communication, I understand it to be engaged with rendering the otherwise unknowable into sensible phenomena. In effect, it offers new models of connection that leverage the poetic function of technology rather than treating technology as a medium for poetics. As a project that emerged in the pandemic, I think of Another Autecology as fundamentally concerned with studying how one responds to crisis. Certainly, this changing, durational experiment has shifted the way I relate to my sense of home. It has radically defamiliarized and then refamiliarized what I know. How does one register changes in the landscape of home? What kinds of events and repetitions would have to happen to make change visible? How do scientific and poetic forms of repetition relate to each other? I started to understand that an important part of my project had to be rewriting the letters of autecology into a space of artistic reclamation.

It is through the context above that I came to describe my project in the following terms: working in dialogue with Henry S. Fitch’s Autecology of the Copperhead (1960) and A Kansas Snake Community (1999) and drawing on practices both within and outside scientific knowledge making, Another Autecology of the Copperhead is an experimental rewriting project that involves following nocturnal pit viper routines in July in order to track a particular species relationship through a series of new technical and epistemological ecologies.

Lab Notebook Prototyping

“Art museum on one side & a science frontier research lab on the other.”

— Lee Lozano, Private Book 5

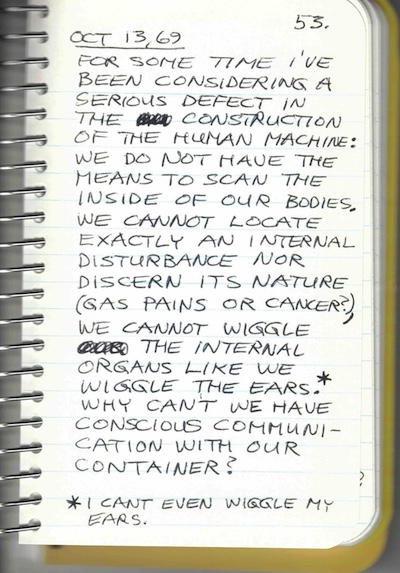

I adore Lee Lozano’s jubilant note-taking practice.

Her notes, which almost always include the date, resemble lab notebook writing. Sometimes, in fact, she writes in actual lab notebooks. Known as a conceptual artist and perhaps most famous for dropping out of the New York scene and moving home to Texas at what could have been the height of her fame, her work is not generally considered in the context of her deep investment in physical science or her serious sense of experiment as an iterative, transformative artistic form. Just as a scientist collages documentation, data, samples, spectra, and repetitive experimental operations in a lab notebook, Lozano documents her life and ideas meticulously in her notes, as if she can only sustain herself through continuous writing. In the process, she proves herself to be self-experimental to a fault. My project on Lozano’s work is oriented toward prototyping her ideas as apparatuses or wearable tech, treating her notes as if they were truly meant to be received as lab notebook writing. That is, I imagine that her ideas were written to be reiterated and reinhabited in ways that manifest her scientific sensibility and commitments as an artist while going beyond the possibilities for meaning in their moment.

My approach to Lozano’s work began with close study of the published facsimiles of her nine small memo books. She uses these memo books as diaries, day planners, and commonplace books in which she jots down addresses, phone numbers, random thoughts, unit conversions, conversation snippets, reading reflections, unattributed quotes, event reviews, and up-to-the-minute commentary. Her notes from 1968 to 1970 cover more than 300 tiny pages. These are not the notes of an ingénue just landing on the scene; Lozano is 37 when she begins Book 1, 39 when she completes Book 9, and 41 when she edits the entire series of notebooks. She changes her process in Book 4, leaving the back of each page blank for adding notes later.

Her notes are detailed, passionate, funny, endearingly odd, and wide ranging in focus. She moves quickly between topics and emotional registers. Ideation is her practice. What do these notes include? A table documenting her daily cigarette consumption, a contentious exchange with her vacuum cleaner (spoiler: it sucks), new origin stories for bodily functions (“Stomach gurgling is really the sound of our whole digestive tract laughing hysterically at us”), and acknowledgments of precarious mental state (“my mind snapped, my ribbon reversed”). She sometimes makes definitive statements and then refers back to them later, conscious that she is contradicting herself. On May 2, 1968, for example, she writes, “I decided that I do not want to live with a man (or anybody else).” She follows up on this statement a year later: “Maybe it’d be fun to live with a man again providing we each had our own separate place also.” Sometimes she addresses a particular friend, and it is unclear whether she is documenting an actual conversation, making a note-to-self for later, or projecting herself into a conversation and improvising her friend’s presumed response. In other words, we do not know much about the context for many of her notes, even though they often suggest conversational immediacy: “Ed, do you think I’d be bullshitting too much if I said I was studying mathematics? It’s more like I’m studying mathematicians.” (Bk 9, p. 33).

Writing in her notebooks often seems to provide a consciously discontinuous framework for wandering within her mental processing that only later resurfaces into an empirical situation that can prompt a new art-life piece. Levity and continuity of work certainly intercede to buoy difficult moments throughout her notebooks, however. This is an artist who—with a serious wink—calls herself a “highentist.” “Continue to work on getting rid of gravity,” she writes on Jan 3, 1970. Lozano’s commitment to these kinds of idealistic statements is notable; she clearly goes through extremely difficult times. Even as she deals with financial hardship, for example, she documents it as part of her work. (She proposes LETSF—or, the Lozano Emergency T.S.* Fund—where T.S. stands for “tough shit you’re out of cash” (Language Pieces).

Lozano takes science seriously. And she takes play with scientific concepts and sources seriously. As an undergraduate, she trained in physics. She references Physics Today, Scientific American, The Physical Foundations of General Relativity, and more in her writing. And while her art practice necessitates that she “compromise” herself repeatedly by subjecting herself to self-experimental conditions imposed by daily life, she is notoriously uncompromising in her choice of materials. Finding out that her favorite paints are going out of production leads her to completely rethink the future of her art practice: “re the discontinuing of shiva standard line of ferrous colors: undercurrent of excitement at prospect of being forced to make a change due to circumstances entirely beyond my control” (Book 2, p. 29). Later, she writes, “Decision that I will stop painting when the shiva standard oil ferrous line of colors runs out” (89).

Despite multiple references in her notebooks to various conditions that would lead her to give up painting, she seems genuinely inspired by everything. And sometimes that tendency toward inspiration and ideation gets in the way of expected etiquette. Reporting on a conversation with Richard Serra, her friend and an artist she respects, for example, she gives a somewhat brutal review of the opening of his solo exhibition at Castelli Warehouse in late 1969 that includes her thoughts on what she would have done differently.

Dec 16, 69

Serra’s warehouse show did not give a trip. Some of the pieces were exciting & most of the people were uptight (till I passed the grass, maybe.) The show looked like “art floor,” dept store. (Why not set up that show in a real warehouse with huge crates or such?). Ropes made it worse.Dec 17, 69

Serra called & I told him some of this but not the real warehouse idea which I just now got. (Bk 5, p. 15-16)

Her notes also indicate rapid shifts in her fortune as an artist as well as the degree to which her projects contribute to her well-being, or not. Following an enthusiastic proposal for a utopian project and clear hopefulness about its realization, for example, her relationship to her work takes a sharp turn:

My work (Grass, No-Grass, Genl Strke, Dialogues) is making me insane. The last three days have brought out my insanity neatly. I think everybody else is a little insane too, but I realize tonight that my image of how the world is, is inaccurate. Part of my insanity is violent paranoia attacks. My phone went dead, (no one called except Dan), I got no mail, & the mental dissolution was immediately precipitated. Then tonight, three days later, a flurry of activity & I instantly feel better. Right now I seem to be dependent on communicating with people for my mental health. It is some need to get info out, to engage, not to brood. (Book 2, p. 80)

Lozano acknowledges significant vulnerability and insight here as she reflects on the importance of social interaction, even as she also references a significant but unspecified break with “my image of how the world is” and its subsequent impact. We do not have access to more information about what feeling “insane” means for Lozano either, though she mentions that it involves paranoia. Regardless of cause or manifestation, she adds a note on the opposite page, shifting the project toward repair and self-protection rather than declaring an end to the piece. Continuation of the work becomes the act of making a safety plan:

Paranoia Kit Piece

Make a Paranoia Kit & keep it around for use (or reference) when you feel an attack coming on. (80A)

Lozano seems to be highly affected by her environment. As a result of this aspect of her being, she has to carefully choose the environments in which she immerses herself and participates. Sometimes, it seems, this sensitivity needs to be protected. Other times, though, it seems to offer her access to scales of experience beyond the human.

Her notes implicitly model her ethical commitments without moralizing or imposing them on others. For example, notes such as “all weapons are boomerangs” and “don’t hit back without love” suggest Lozano’s rejection of intentional violence. Humor is a tool she uses to diffuse the imposition of end-directed controls and to disrupt normative modes of perception surrounding mundane everyday experiences with an earnest grappling that often emerges, counterintuitively, through the artifice of her project setups. In this way, her approach to everyday phenomena and devotion to actively generating experiences of wonder within the ostensibly mundane everyday overlaps with something like Bernadette Mayer’s “Found poems” prompt in The Art of Science Writing (1989): “a specimen, no matter how mundane or small, removed from its context and examined closely, becomes much more interesting. When it is returned to its context, the context becomes more interesting, too” (73). Sometimes Lozano herself is the specimen, but she always seems determined to forge physical connections to nonintuitive, and nonhuman, matters of daily life.

Two themes in Lozano’s writing are of particular interest to me: her invocations of nonhuman forms of embodiment and her commitment to technologically-mediated forms of transparency. Her work is always closer to critical anthropomorphism than it is to a simple translation of phenomena to human use or control. And with regard to transparency, her straightforward way of communicating (quite nicely) obscures the complexity of her suggestions for procedures that might make something more transparent:

Middle-of-the-night thoughts: “Random cant-sleep-due-to-brain-overload-thoughts: since I’ve been consuming much more oil in my diet (& on my body) I seem to be getting more transparent. (oil spots on paper are transparent, etc). Want more transparency! (See Light Piece & fantasy abt matter becoming more transparent the more light on it. Also description of lit rose, Physics Today BK review) Emotions/needs/ideas —> More transparent! (Book 7)

Here, she is likely registering a connection between oil paints and oil-based foods, and she seems to instinctively rethink that connection in terms of how they might be juxtaposed to produce forms of literal and figurative transparency. Lozano repeatedly expresses interest in accessing the inside of the “human container” in new ways. That is, she clearly values a straightforward definition of transparency even as she seems to acknowledge the layers of mediation or augmentation that might be necessary to achieve it. One aspect of her work that interests me quite a lot is the way she seeks alternatives to language for communicating what is happening inside the body emotionally or physically. She seems motivated by a desire to access every scale of experience and to create novel ways of scaffolding and networking communication between interior and exterior.

In keeping with Lozano’s investment in physical science generally and molecular and atomic scales more specifically, though, she is amusingly unconvinced by any suggestion of the human form’s evolutionary excellence:

Whoever or whatever designed human beings and all evolutionary forms that led up to them was a bad artist who took the idea of form follows function to its ultimate disaster. Any rumination about mankind’s shape will disclose how exceedingly ugly a human is. The silly little head on a great gawky body, the separateness of front & back, the unrelated protuberances, mounds, angles, hollows, the embarrassing vulnerability of the eyes & genitals, the dead & stupid blankness of the back of the head … If we were more intelligent we would be shaped like spheres which at rest had perhaps smooth reflective surfaces. We could change from solid to liquid to gaseous states of matter or become nothing but a charge or a force. Our material & color would vary at our will, we’d roll, float or fly. (Book 1)

She elaborates on these notes elsewhere on the same day, and the extended version is collected among her Language Pieces. An edited version of the paragraph above becomes her “Prologue,” and what follows it is a more substantive dive into what she calls “redesign the human being suggestions”:

Substitute a dashboard or a control panel for the face. Let it be easily accessable for scanning by the host as well as other beings. On the control panel are gauges & dials indicating continuously changing states of temperature, respiration, metabolism, pulserate, heartbeat, adrenalin count, gonad charge, balance & many other body systems. This info being readily accessible to all might eliminate the peculiarly human habit of telling lies, the tiresome question “how are you?”

In my own work, I treat Lozano’s ideation as the groundwork for building prototypes. That is, I propose to bring her writing into the context of bioengineering, asking how she might have enacted a proposal like the one above while also incorporating implicit features of her notebook writing into the model. Amplifying Lozano’s investment in self-experiment as well as her desire to never “lessen” anyone, I interpet her work as fundamentally concerned with generating circuits of care. In her life, however, Lozano’s model of care was not particularly self-sustaining. My experiments will attempt to complicate the connections between the circuitry of her proposed device and the living organism it measures (Lozano), orienting experiments toward harnessing bioelectricity and generating transformative feedback loops in ways that draw from current experimentation in user-device design.

This project aims to manifest Lozano and then more Lozano. Lozano squared. My approach to her work is similar to my approach to the work of other artists and scientists: rather than dismissing a notebook full of ostensibly strange ideas, what if we took them seriously in carefully-selected contexts? What new sense could be made? In the case of Lozano: why have authenticity on one scale when you can have (weirder) authenticity on multiple, potentially competing scales? (“How are you?”) Could it add up to new modes of relating to each other? I think of myself as caring for Lozano’s distinctive note-taking practice by noticing themes and features that she may not have noticed herself when she was writing in the moment; then, I amplify those features and feed them back into her work as a model of interventional, retroactive collaboration.

Lozano clearly never invests much in the culture of celebrity or fame, and despite criticism and speculation regarding her mental state, she lives out the ethics to which she commits herself. Perhaps as a result, the physics of everyday life and suggestions for alternative embodiment and participation in dailiness that animate her notebook pages never actually materialize as significant throughlines in her work. What she leaves behind in her notebooks, however, is the outline of unpursued experimental trajectories artist-scientists today can pick up, reference, and adapt. Through her self-sampling and sustained interest in matter, for example, she repeatedly glimpses the beginnings of alternative sign systems and pushes to make that project legible, at least to herself, in the context of existing frameworks. Undoubtedly, this research trajectory would have been richer had she pursued and documented it herself in the context of her idiosyncratic version of everyday physical science. When she is writing at arguably her most interesting, I think, she directs sustained attention to the physical world, reimagining the terms of human sociality and connection from the strange groundwork of these observations.

Stereopoetry

“Science is practical in the highest sense of the word.”

— J.H. van’t Hoff, Imagination in Science

For a long time, I have been fascinated with molecular shape. A carbon atom, for example, can be linear, planar, or tetrahedral. Relatedly, I am drawn to a particular moment in the history of science: the emergence of stereochemistry as a field within structural organic chemistry in the late nineteenth century. With the proposal for the tetrahedral shape of carbon, J.H. van’t Hoff intervened into the trajectory of the discipline, making consideration of the spatial arrangement of atoms (rather than just connectivity) into a new fundamental on which to build an understanding of molecular interactions and reactivity. New terms emerged, like “enantiomer” and “chirality.” Later, this proposal would become a new basis for modern biochemistry, as the body is composed of single-enantiomer chiral molecules—meaning molecules that are nonsuperimposable mirror images and therefore have a particular orientation in space, like the right and left hand. See also: Robert Smithson’s Enantiomorphic Chambers (1965).

In the language of organic chemistry, connectivity dictates shape—connectivity is analogous to shape—and without its thorough consideration, one cannot understand the bigger picture of higher order function and meaning. I am motivated to return to fundamental considerations of the matter of language, scientific experiment, and a broad concept of shape beyond the referential field of the human, on the one hand, as well as a commitment to exploring the concepts of conservation, pataphysics, and the recycling of scientific concepts, on the other. With this motivation in mind, I conceptualized a project, which I plan to present alongside student work in the spring exhibition for the class I’m currently co-teaching, that returns not only to the details of van’t Hoff’s theory of the tetrahedral carbon as a site for proliferating concepts of reading and poetic meaning-making but also to the way he shared his theory—foldable cardboard models sent through the mail—to convince other scientists of the validity of his proposal. Essentially, my intention is to take the groundwork of his theory seriously in a different context. The relationship between atoms in space becomes the context for new alphabets of relation. It is an argument—building on the work of others—for new substance.

Some personal history guides me: in my first semester of graduate school, I wrote an essay historicizing the concept of imagination across literary and scientific texts for my cohort’s proseminar. (At the time of the presentation, I think I was 22 years old). I did a hybrid science-lit talk that included drawing molecular models on the board. I remember the room getting pretty quiet afterward. We had been talking about literary theory all semester. Finally, a friend gently suggested that I should return to Derrida’s critique of Lévi-Strauss. She was too nice to say so explicitly, but the implication was that my project was hopelessly regressive in its attempt to collide a key moment in the history of structural organic chemistry with key moments in literary theory. I was becoming an advocate for something that had already been disproven. I trusted my friends, and my proposal was by no means perfect, so I put aside the thought of this mode of exploration. And I was able to complicate my views as I became more disciplined.

Yet, I also hoped to have support for my work that would allow me to hold onto this interest in real scientific practice while exploring something that could actually mobilize its possibility. (The relationship between structuralism and shape means something different in the context of literature versus the context of molecules). And I never lost my energy for, and attentiveness to, moments when a person encounters a new-to-them field without any immersion in its taken-for-granted fundamentals and presents a natural yet radical alternative vision. New fields can form or organize this way. This enduring commitment to interdisciplinary encounters forms a crucial pillar of my approach to pedagogy. I often work with students who are trying to navigate their passion for serious considerations of scientific practice in the context of art while also grappling with a desire for a space to experiment with queering this practice in various ways. When one works in a space or a sign system that can quickly, and incorrectly, subsume novelty under existing frameworks, I have found it to be essential to find supporters who will hold space for possibility. “What you have to do is generate the criteria for your own reception,” I say, always properly attributing the quote to my training, and then I watch with pleasure as my students react with enthusiasm to this prospect, usually writing down the instruction.

Now, I would like to turn somewhat abruptly to the significant and peculiar moment in the history of structural organic chemistry that I referenced above as a way of emphasizing my enthusiasm for my project while also acknowledging that similar orientations already exist but may not frame themselves as projects with a connection to science or scientific controversy. Alan J. Rocke’s sympathetic book on German chemist Hermann Kolbe is particularly helpful in drawing attention to the circumstances surrounding the controversial reception of van’t Hoff’s theory of the tetrahedral carbon:

A sketch of the theory was published in Dutch in 1874, and a longer French version appeared the next year. The first enthusiastic advocate of van’t Hoff’s theory was Johannes Wislicenus, professor at Würzburg, who was a mid-career structural organic chemist with a fine reputation; he had even published some thoughts on three-dimensional (physical) isomerism himself. Wislicenus asked his student F. Hermann to prepare a German translation of van’t Hoff’s “Chemistry in Space,” wrote an enthusiastic preface, and sold the work to Vieweg Verlag. Kolbe found out about this translation almost immediately because the Vieweg company had a long-established policy of automatically sending proof sheets of all their organic-chemical publications to Kolbe. (328)

Kolbe, with no personal justification for disliking van’t Hoff, therefore encounters the theory early in its reception. In response, he publicly (in print) mocks, taunts, and pathologizes van’t Hoff. Consistently, he attacks where he perceives weakness. While I am reluctant to emphasize Kolbe’s sustained criticism, I do want to draw attention to the details of the situation’s unfolding in order to then refocus attention on the way van’t Hoff later incorporates this critique into his position on the nature of experimentation. As Rocke points out, van’t Hoff embodied a particularly infuriating form of researcher to Kolbe: “Kolbe found his ideal model for the ‘metachemist’ pursuing ’transcendental chemistry’ when the then-unknown J.H. van’t Hoff unveiled his theory of the asymmetric carbon atom, the first step toward chemistry considered in three dimensions—soon to be called stereo-chemistry. Van’t Hoff, who had studied with Kekulé and Wurtz, first found employment at the Utrecht Veterinary College…” (328).

Famously, Kolbe takes aim at van’t Hoff in lively, personal terms:

A Dr. J.H. van’t Hoff who is employed at the Veterinary School in Utrecht appears to find exact chemical research not suiting his taste. He deems it more convenient to mount Pegasus (apparently borrowed from the Veterinary School) and proclaim in his ‘La chimie dans l’espace’ how, in his bold flight to the top of the chemical Parnassus, the atoms appeared to him to be arranged in cosmic space. (329)

In other words, Kolbe clearly has great fun with van’t Hoff’s inferior position. (The modern-day equivalent of such a status-oriented dismissal might be something like using the term “adjunct professor” as a pejorative, though we might expect it to be less memorable than the image Kolbe offers). He states that van’t Hoff’s pamphlet “teems with fantastic trifles” and “it is completely impossible to criticize [it] in any detail because the fancy trifles in it are totally devoid of any factual reality and are completely incomprehensible to any clear-minded resarcher” (6-7). “It is a sign of the times,” he writes, “that modern chemists feel the urge and capability to have an explanation for everything and if gained experience does not suffice, then they are perfectly happy to invoke supernatural explanations” (7). Even Wislicenus, mentioned above for his good reputation, becomes a figure Kolbe can use to dismiss van’t Hoff before reversing the poles and thoroughly dismissing Wislicenus:

As already stated, I would have ignored this paper if not, incomprehensibly, Wislicenus had provided it with a preprinted preface in which he, by no means jokingly but quite seriously and warmly, recommended this paper as meritorious accomplishment …. Wislicenus therefore declares herewith that he has withdrawn from the ranks of exact natural scientists and changed over to the camp of the natural philosophers of ominous remembrance, which are only separated by a thin “medium” from the spiritualists. (7-8)

As Rocke demonstrates, the controversy becomes a key topic in the scientific correspondence at the time. Wislicenus, in fact, intervenes directly on van’t Hoff’s behalf in an 1877 letter to Kolbe:

You cannot possibly have studied van’t Hoff’s essay … [for] how else could you have reproached me (by logic I do not understand) for a tendency toward spiritualism, or held against the young van’t Hoff his position at a veterinary school, or against the translator Herrmann, who was my assistant and solely due to pressing external circumstances accepted a position at the agricultural institute in Heidelberg! I have never doubted that it is a holy zeal for the truth that guides your critical pen; but on the other hand I regret that you do not seem to concede any possibility of your own fallibility, which everyone must grant … I know that I can err, but I also know that I have no cause to allow myself to be struck from the ranks of exact scientists, for I as well as you have the will to serve the truth … (332-33).

Kolbe elsewhere rails against August Kekulé—who is now perhaps most well known for dreaming of a snake eating its tail and then conceptualizing the ring shape of benzene—which draws Kolbe’s former student Jacob Volhard into the fray:

And as for the form, I ask you: What do you care about Kekulé’s style or his classical education? Consideration for K’s scientific accomplishments, indeed mere collegial respect ought to have stopped you from treating this man as if you were a teacher looking over a schoolboy’s assignments and correcting his mistakes …. I beseech you, no more such intemperate critiques! More tolerance and respect for scientists who have made and are still making their contributions! (332)

Time and time again, Kolbe begins with an assumption about the right answer and correct outcome, then he exerts his authority and control to enforce his worldview regardless of the cost. But, importantly here, he ends up being wrong about the science. A new field was taking hold.

Van’t Hoff most famously addresses Kolbe’s criticism in 1878 in the inaugural lecture upon his appointment to the faculty at the University of Amersterdam. He calls this lecture Imagination in Science. To begin, he reads Kolbe’s criticism in full. Then, he pivots:

Here is not the place to discuss further this vast divergence of views; nevertheless, I have mentioned it, since it formed the main reason for the choice of my subject: Imagination in Science

In the first half of his talk, van’t Hoff defines experiment and asserts its value. That is, he does not spend any time arguing for the validity of his theory of the asymmetric carbon or directly championing it. Kolbe’s main problem with van’t Hoff seems to be the lack of what he considered to be sufficient empirical evidence to support a paradigm-altering theory. Van’t Hoff’s theory was indeed based on published—and therefore very real—experimental data. Kolbe, circumscribing the terms of the possible, essentially puts forward the argument that van’t Hoff did not have the kind of impressive university position or experience in the discipline that would be necessary to truly understand the limits of the field. Concomitant with an understanding of the limits of the field would be an understanding of the limits of knowledge. Thus, what seemed to particularly anger Kolbe was the “insolence” with which van’t Hoff synthesized published data in order to project to a new theory and therefore a new domain of experimentation and investigation. Van’t Hoff’s theory threatened not only Kolbe’s worldview but also his methodology. Experiment, in other words, was Kolbe’s domain.

Van’t Hoff begins by directly addressing the definition of experiment, summarizing the scope of his talk as “The role of the imagination in investigating the connection between cause and effect” (8). He situates the terms of experiment as he understands them and presents examples from the history of science that illustrate limit cases and innovations. He references the logic by which Helmholtz invented the ophthalmoscope, for instance, to exemplify a productive “synergism of imagination and critical judgment”:

There is a difficulty which makes it impossible to observe the retina through the pupil although the latter is completely translucent. The difficulty is that precisely during observation, as the idiom states, one stands in one’s own light. A flame put between the observed and the observing eye would illuminate the former but make its observation impossible. The thought occurred to HELMHOLTZ’s mind to place between both eyes a small mirror with a small aperture in such a way that a lateral light beam would fall in the subject’s eye which now can be observed through the aperture. (9-10)

Imagination, van’t Hoff argues, “plays a role both in the ability to do scientific research as well as in the urge to exploit this capability” (12). Summarizing the results of an inquiry into the biographies of famous scientists across history, he points out that two criteria characterize the scientists who contributed the most significant theories and discoveries to their fields: first, artistic inclinations, and second, (what van’t Hoff calls) the diseased imagination (15).

With regard to the former, he surveys great scientists’ enthusiasm and talents for poetry, storytelling, and theatre:

HAÜY (BUCKLE, Miscellaneous Works. I. 10): “He was essentially a poet, and his great delight was to wander in the Jardin du Roi, observing nature, not as a physical philosopher, but as a poet. Though his understanding was strong, his imagination was stronger.”

With regard to the latter, he notes that “examples of the most bizarre imagination, superstition, spiritualism, hallucinations, even insanity, occur not infrequently in the examined biographies (15-16). As he continues, the examples become quite strange: “Newton always was afraid that an accident would befall him in a carriage and thus held himself onto the door. Kepler’s conception of the universe was most peculiar; he seriously believed the earth to be a reptile and that the planets which surround the earth produce a melodious chord by their movement (Jupiter and Saturn form the bass, Mars the tenor, and so on).”

Finally, van’t Hoff turns to the current state of scientific research, arguing that the expanding field of researchers changes both the pathway to scientific discovery and the role of the imagination in conducting scientific work. Imagination has become less obviously necessary to the scientific enterprise: “If the diaphragm, which plays the predominant role in breathing, is artificially paralyzed, then the chest takes over for a while the work of the diaphragm as best it can. If imagination is lacking, then one tries by other means to compensate for this deficiency” (17).

He concludes the talk with a comparison between two scientists:

At the end of a biography CUVIER once compared two great chemists, VAUQUELIN and DAVY; he expressed himself about as follows: “Notwithstanding his innumerable investigations and in spite of the important and noteworthy observations with which VAUQUELIN enlarged the stock of scientific knowledge, he cannot be considered as of the same caliber as DAVY. The former put his name in the paragraphs; the latter in the titles of each chapter. In a completely unpretentious manner, the former observed with a lantern the smallest obscurities and penetrated into the darkest nooks; the latter ascended like an eagle and illuminated the large realm of physics and chemistry with a shining beacon.” (18)

Following this comparison between the experimental contributions of Vauquelin and Davy, van’t Hoff expresses unmitigated optimism:

I make these words my own in order to describe what research is without imagination, and what it can be if one uses it in an admissible manner. VAUQUELIN did not appear in the two classifications above; DAVY, however, did in both as poet as well as visionary. His discoveries were the fruits of that great gift which [H.T.] BUCKLE describes: “There is a spiritual, a poetic, and for aught we know a spontaneous and uncaused element in the human mind, which ever and anon, suddenly and without warning, gives us a glimpse and a forecast of the future, and urges us to seize the truth as it were by anticipation.” (18)

Sources

Henry S. Fitch’s Autecology of the Copperhead (1960); Lee Lozano’s Language Pieces (2018); Lee Lozano’s Private Books (wr. 1968-70, ed. 1972; pub. 2021); Alan J. Rocke’s The Quiet Revolution (1993); J.H. van’t Hoff’s Imagination in Science (pub. 1967)

Image sources: Edward Packard’s You are a Shark (1985); May 14, 1968 note in Lozano’s Private Book 1; July 1, 2022 copperhead and cicada photo by Kristen Tapson; plate 20 from Fitch’s Autecology; July 12, 2021 copperhead photo by Kristen Tapson; Oct. 13, 1969 note in Lozano’s Private Book 4; cover of a personal copy of Imagination in Science